Automation or automatic control is the use of various control systems for operating equipment such as machinery, processes in factories, boilers, and heat treating ovens, switching on telephone networks, steering, and stabilization of ships, aircraft and other applications and vehicles with minimal or reduced human intervention. Some processes have been completely automated.

Automation has been achieved by various means including mechanical, hydraulic, pneumatic, electrical, electronic devices and computers, usually in combination. Complicated systems, such as modern factories, airplanes, and ships typically use all these combined techniques. The biggest benefit of automation is that it saves labor; however, it is also used to save energy and materials and to improve quality, accuracy, and precision.

The term automation, inspired by the earlier word automatic(coming from automaton), was not widely used before 1947 when Ford established an automation department.It was during this time that industry was rapidly adopting feedback controllers, which were introduced in the 1930s.

Open-loop and closed-loop (feedback) control

Fundamentally, there are two types of the control loop; open loop control, and closed loop (feedback) control.

Open loop control

In open loop control, the control action from the controller is independent of the “process output” (or “controlled process variable”). A good example of this is a central heating boiler controlled only by a timer, so that heat is applied for a constant time, regardless of the temperature of the building. (The control action is the switching on/off of the boiler. The process output is the building temperature).

In closed loop control, the control action from the controller is dependent on the process output. In the case of the boiler analogy, this would include a thermostat to monitor the building temperature, and thereby feed back a signal to ensure the controller maintains the building at the temperature set on the thermostat. A closed loop controller, therefore, has a feedback loop which ensures the controller exerts a control action to give a process output the same as the “Reference input” or “set point”. For this reason, closed loop controllers are also called feedback controllers.

The definition of a closed loop control system according to the British Standard Institution is ‘a control system possessing monitoring feedback, the deviation signal formed as a result of this feedback being used to control the action of a final control element in such a way as to tend to reduce the deviation to zero.

Likewise, a Feedback Control System is a system which tends to maintain a prescribed relationship of one system variable to another by comparing functions of these variables and using the difference as a means of control.

The advanced type of automation that revolutionized manufacturing, aircraft, communications and other industries, is feedback control, which is usually continuous and involves taking measurements using a sensor and making calculated adjustments to keep the measured variable within a set range. The theoretical basis of closed loop automation is control theory

Control actions

The control action is the form of the controller output action.

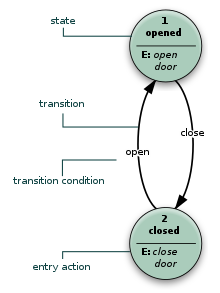

Discrete control (on/off)

One of the simplest types of control is on-off control. An example is a thermostat used on household appliances which either opens or closes an electrical contact. (Thermostats were originally developed as true feedback control mechanisms rather than the on-off common household appliance thermostat.)

Sequence control, in which a programmed sequence of discrete operations is performed, often based on system logic that involves system states. An elevator control system is an example of sequence control.

PID controller

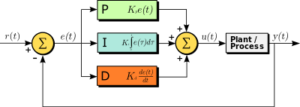

A block diagram of a PID controller in a feedback loop, r(t) is the desired process value or “set point”, and y(t) is the measured process value.

Proportional–Integral–Derivative controller(PID controller)

PID is a control feedback widely used in the industrial control system. A PID controller continuously calculates an error value {display style e(t)} as the difference between the desired set point and a measured process variable and applies a correction based on proportional, integral, and derivative terms, respectively (sometimes denoted P, I, and D) which give their name to the controller type.

The theoretical understanding and application date from the 1920s, and they are implemented in nearly all analog control systems; originally in mechanical controllers, and then using discrete electronics and latterly in industrial process computers.

Sequential control and logical sequence or system state control

Programmable logic controller

Sequential control may be either to a fixed sequence or to a logical one that will perform different actions depending on various system states. An example of an adjustable but otherwise fixed sequence is a timer on a lawn sprinkler.

State Abstraction

States refer to the various conditions that can occur in a use or sequence scenario of the system. An example is a elevator, which uses logic based on the system state to perform certain actions in response to its state and operator input. For example, if the operator presses the floor n button, the system will respond depending on whether the elevator is stopped or moving, going up or down, or if the door is open or closed, and other conditions.

An early development of sequential control was relay logic, by which electrical relays engage electrical contacts which either start or interrupt power to a device. Relays were first used in telegraph networks before being developed for controlling other devices, such as when starting and stopping industrial-sized electric motors or opening and closing solenoid valves. Using relays for control purposes allowed event-driven control, where actions could be triggered out of sequence, in response to external events. These were more flexible in their response than the rigid single-sequence cam timers. More complicated examples involved maintaining safe sequences for devices such as swing bridge controls, where a lock bolt needed to be disengaged before the bridge could be moved, and the lock bolt could not be released until the safety gates had already been closed.

The total number of relays, cam timers, and drum sequencers can number into the hundreds or even thousands in some factories. Early programming techniques and languages were needed to make such systems manageable, one of the first being ladder logic, where diagrams of the interconnected relays resembled the rungs of a ladder. Special computers called programmable logic controllers were later designed to replace these collections of hardware with a single, more easily re-programmed unit.

In a typical hard wired motor start and stop circuit (called a control circuit) a motor is started by pushing a “Start” or “Run” button that activates a pair of electrical relays. The “lock-in” relay locks in contacts that keep the control circuit energized when the push button is released. (The start button is a normally open contact and the stop button is normally closed contact.) Another relay energizes a switch that powers the device that throws the motor starter switch (three sets of contacts for three phase industrial power) in the main power circuit. Large motors use high voltage and experience high in-rush current, making speed important in making and breaking contact. This can be dangerous for personnel and property with manual switches. The “lock in” contacts in the start circuit and the main power contacts for the motor are held engaged by their respective electromagnets until a “stop” or “off” button is pressed, which de-energizes the lock in the relay.

Commonly interlocks are added to a control circuit. Suppose that the motor in the example is powering machinery that has a critical need for lubrication. In this case, an interlock could be added to insure that the oil pump is running before the motor starts. Timers, limit switches, and electric eyes are other common elements in control circuits.

Solenoid valves are widely used on compressed air or hydraulic fluid for powering actuators on mechanical components. While motors are used to supply continuous rotary motion, actuators are typically a better choice for intermittently creating a limited range of movement for a mechanical component, such as moving various mechanical arms, opening or closing valves, raising heavy press rolls, applying pressure to presses.